Dancing

with Everything

Resist the Chaos; Reclaim Community!

|

|

The Art of Grieving on Substack!

I came to writing later than most people if we don’t count writing in a private journal, and the invitation to write that I got from Sister Mercia, my 9th grade home room teacher at Sacred Heart Academy in Louisville Ky. She saw her role as a teacher to be one of identifying students’ gifts and encouraging them to develop them, (not ignoring or burying then like one of the foolish characters in Matthew’s Parable of the Talents.) As my English teacher, Sister saw my early writing attempts and skills and encouraged me to pursue writing as a career. It’s worth noting, she was also my Algebra teacher, and it was obvious there was no likely career path there. But I was already a dancer, an art one must pursue while young. By the time I was in her class I already had my 10,000 hours in towards mastering that profession. When she saw me dance, she saw the wisdom in my decision, but she made me promise to come back to writing when my time on the stage came to its natural end.

I came to writing later than most people if we don’t count writing in a private journal, and the invitation to write that I got from Sister Mercia, my 9th grade home room teacher at Sacred Heart Academy in Louisville Ky. She saw her role as a teacher to be one of identifying students’ gifts and encouraging them to develop them, (not ignoring or burying then like one of the foolish characters in Matthew’s Parable of the Talents.) As my English teacher, Sister saw my early writing attempts and skills and encouraged me to pursue writing as a career. It’s worth noting, she was also my Algebra teacher, and it was obvious there was no likely career path there. But I was already a dancer, an art one must pursue while young. By the time I was in her class I already had my 10,000 hours in towards mastering that profession. When she saw me dance, she saw the wisdom in my decision, but she made me promise to come back to writing when my time on the stage came to its natural end.

Making a living as a dancer did come to an end after several seasons of summer stock, work in nightclubs and a movie, and the national touring company of Once Upon a Mattress. When I became pregnant, and my then husband accepted a job in Detroit, I lived far away from places like New York and LA where professional dancers, actors and musicians could make a living. I was left to dancing as an avocation–teaching and performing in Festival Dancers, a dance company out of the Jewish Community Center. We danced in churches and synagogues, art museums and street fairs, and I eventually got a social work degree and becoming a professor and therapist, I used the expressive arts with students and clients.

While managing a behavioral health care clinic I returned to writing and created my first book, Stillpoint: The Dance of Self-Caring Self-Healing. Currently in its second edition it’s now a popular weekly online course. My second book, Warrior Mother: Fierce Love, Unbearable Loss and the Rituals that Heal came about after many losses, the death of two adult children and my best friend, where I used the arts of dancing, storytelling, and writing to process these experiences of loss. Through this, and teaching performing using the art-based tools of InterPlay helped me to discover ways to turn grief into gift.

Turns out that art and art-making surprise us, and that’s invigorating. We’re inspired and energized by art that is done for us, on our behalf. And when we create something ourselves that hadn’t existed before, these activities put us in touch with what I call, “the part of us that’s smarter than we are.” Einstein referred to this creative, intuitive part as a “sacred gift” for which “the rational mind is a faithful servant.” Since that’s not how it is in our culture very often, that’s what we’ll be doing in this space–calling on the arts and art-making to help us transform loss and make art out of what happens to us.

Einstein scolds us that “We have created a society that honors the servant and has forgotten the gift.” With the help of readers and collaborators, in this space we will view grief as a gift, and using the arts, take steps towards solving the problems of the world Einstein noted could not be solved “from the same level of thinking we (as a society) were at when we created them.” Hopefully as we’re using the arts to process our own individual and communal grief, this “multidimensional perspective” that Einstein recommends will change us and our culture in the direction that supports everyone living their best lives.

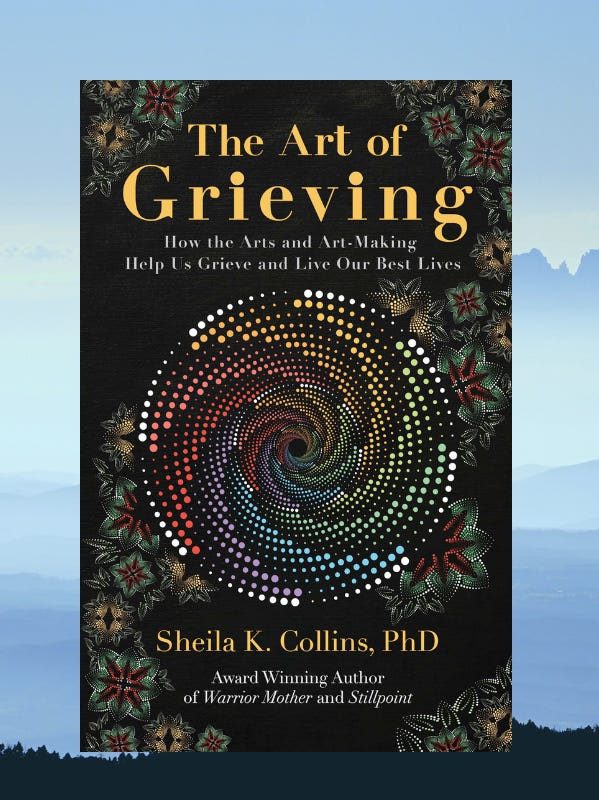

This post is my first offering on Substack. I’ve been lurking about and circling around the platform, reading and admiring its many talented writers and thought leaders, people who majored in English literature or journalism in college, who’ve written for major newspapers, and authored dozens of best-selling books. I’ve been writing a weekly blog, “Dancing with Everything” and sharing it through this blog and Constant Contact faithfully for a decade. That writing practice and the responses and comments I received from readers has made me a much better writer, and a less lonely one. It’s helped me to birth my fourth book, The Art of Grieving: How Art and Art-making Help Us Grieve and Live Our Best Lives. Now. During these final chapters of my life I’ll finally be playing at the grown-up table.

To set up your own Substack profile, follow along, and find more to read, click here. https://substack.com/@danceswitheverything/posts

Grieving for a Country

About a decade ago, I expanded my view of loss and what situations need grieving. I had written a book, Warrior Mother: Fierce Love, Unbearable Loss and the Rituals that Heal that illustrated the grieving of personal and familial situations of loss and touched on the involvement of the larger political/social environment in some of those losses. But what about the occasions when changes occur in the larger political/social environment? Are these situations and the losses they create, something we need to grieve? And what helps us to do that?

About a decade ago, I expanded my view of loss and what situations need grieving. I had written a book, Warrior Mother: Fierce Love, Unbearable Loss and the Rituals that Heal that illustrated the grieving of personal and familial situations of loss and touched on the involvement of the larger political/social environment in some of those losses. But what about the occasions when changes occur in the larger political/social environment? Are these situations and the losses they create, something we need to grieve? And what helps us to do that?

I began a weekly blog that I titled, “Dancing with Everything.” This fit my perspective that much that life hands us does not come in response to our having invited it. This is especially true for the larger scaled events. In that fateful year of 2020, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell got my attention with these words, “None of us has the luxury of choosing our challenges. Fate and History provide them for us.” Throughout the years of this weekly writing practice, I explored what was currently happening in the larger world while asking the question, “Is this a loss that needs grieving?” From what eventually became The Art of Grieving: How Art and Artmaking Help Us Grieve and Live Our Best Lives I was carried back to the beginning concept – to dance with, to make art out of what happens to us, although we didn’t get to pick what that was.

Recent experiences with countries, borders and wars

- When I moved to Pittsburgh in 2005, I asked people where their ancestors immigrated from when they came to work in the steel mills in the late 18th century. Before naming the country –Russia, Czech Republic, Croatia, Hungry, Ukraine or Yugoslavia, they would put the phrase, “Formerly known as.” Since many people came originally with the intention of going back home at some point, it must have been hard to not have a home to go back to. And our country of origin has a strong effect on our identity and where we feel we belong.

- Shortly after war broke out in Ukraine, I was having brunch one Sunday morning with my husband’s family in New York City and learned that both his grandfathers were from villages in Ukraine. For Jewish families particularly, such details have historically made the difference between salvation and demise of the family members and their descendance.

- I was working on the Art of Grieving book when Hamas and other Palestinian militant groups launched the coordinated armed incursions into Israel on October 7th 2023. Over 1000 people were killed and 250 were taken hostage, including 30 children. This attack triggered a war that is still trying to end to have the hostages returned and the people of Gaza relieved of their horrific suffering and the devastation of their surroundings.

- And this week, in the peaceful transfer of power, the United States of America has, as a country moved further from the intentions of its founders –a country ruled by equality under the law with equal freedom and opportunity for all.

So, grieving for a country one loves and is in the process of losing is something deserving of our grief. But like dealing with anything in the larger world, we cannot, and must not, try to do it alone. After the Oct 7th massacre in Israel, David, one of the members of my online InterPlay group who lives in Israel came online for a few minutes from his home. After he left, we decided to finish our time together by dancing on his behalf, which is the InterPlay form we consider a prayer. I wrote about this in the chapter on Sweet Sorrow through the Long Arc of Grieving —

Looking up at the list of songs on my playlist to select one to accompany our dancing for this occasion, the song “Kinder” by the acapella singing group Copper Wimmin caught my eye. I was especially drawn to the album’s title, which I had never noticed before: “The Right to Be Here.” A strong kinesthetic signal in my body confirmed the irony in using this song for this occasion. Wars and armed conflicts are, at their core, a fight over who has a right to live in a particular place or who has the right to live at all.

As the other participants and I followed and led one another through the dance, the song took me to a place that its lyrics suggested. In the face of horrific war, injustice, fear, and death, “I decided to be happy, I decided to be glad, I decided to be grateful, for all I ever had.” We felt those sentiments and sent them to David, remembering what he desires is ‘smiles and soft tones.”

Later that afternoon, I realized how good I had been feeling since the morning visit with David and dancing on his behalf. I began feeling something that grievers often feel, a kind of guilt that we are allowing ourselves to feel good when the loss we are grieving, or that those around us are grieving, is so great. I questioned whether feeling good was the right response to the difficult situations that people I know and people I don’t know are being faced with around the globe.

Just then, a notice came into my email box to join a Community Vigil for Our Collective Pain, sponsored by one of my favorite organizations, Reimagine. Their mission is to host programs that reimagine loss and channel life’s challenges into meaning and growth. I know vigils to be a time of keeping awake, of coming together in silence with others after something horrific has occurred, to slow our responses down to enable clear attention and awareness, to offer prayers for those affected, including ourselves. This opportunity seemed just the right one for me on this occasion. I joined 146 other people online…as we were intent on uniting and grieving our collective pain. That evening, I played the song again for myself and moved to it to reinforce those decisions that the song had caused me to make –“I decided to be happy, I decided to be glad, I decided to be grateful, for all I ever had.”

I ended the chapter with the question, “Could it be the obligation of those of us not living in the center of the storm to keep alive the loving, peaceful energy that the world needs to get us all there?”

Grieving Devastation

We’ve seen it on our screens for days now, the devastation of entire neighborhoods; schools, places of worship, shops, restaurants, and landmarks, all through the eyes of photojournalists whose job it is to communicate and record what’s happening in our larger world. When asked to select and describe their photos, these AP journalists added words.

Here are some of comments on their photos –

- “Having covered dozens of wildfires, some of the largest in California’s history, I immediately knew the scale of destruction was unlike anything I had ever seen.” Ethan Swope

- “One of the biggest challenges in taking this photo was ensuring my safety in such a hazardous environment. The air was thick with smoke, making it hard to breathe… Documenting the aftermath while respecting the emotions of survivors is always a challenge.” Jae C Hong

- “When you hear that thousands of homes have been destroyed, a picture like this reminds you that each of those homes represent the memories collected by the people who live there. For some it stretches back generations.” John Loucher

- “I chose this picture because of the trees. The dramatic light illuminated the yellow caution tape that cordoned off townhomes and trees that had been burned by the Eaton Fire. It was a crime scene. Scorched trees are everywhere. I’m going to keep photographing the trees. They are part of us.” Carolyn Kaster

- “The (broken) statue makes me think of the tragedy of Pompeii. The volcanic eruption turned humans into preserved stone statues. The Southern California fires have turned us headless and homeless. We lay down with our arms crossed motionless in the face of an environmental catastrophe.” Damian Dovarganes

“Devastation” is the word that most fits this situation. We speak of devastation when something has been “brought to ruin by violent action.” This was no ordinary forest fire, but a case of tornado-type winds fanning the flames of a fire fed by acres and miles of exceptionally dry vegetation. As the days have gone on, the situation has fulfilled its promise of what devastation does, “to reduce to chaos” not only the lives of firefighters and families directly involved in fighting or escaping the disaster’s rages, but an entire region of the southwestern United States. As news of the “disorder “spreads across the nation and the world, people recognize our common “helplessness,” to repair what has been destroyed and to prevent such occurrences in the future.

The Many Faces of Loss

When losses occur its helpful to name them accurately. These losses caused by the fires are Traumatic Losses, like those caused by war or other natural disasters like floods. They come suddenly, ‘out of the blue, ‘carrying with them Cumulative Losses on the way to becoming, for many people, Living Losses or Chronic Sorrows. The effects of some losses will endure throughout a person’s life, and beyond, continuing to cause their life to fall short of what they had expected it to be.

It’s extremely helpful when people respond with kindness and compassion, responses we don’t see often enough when things are going well in a community. Rather than asking, “Why Me? Or Why Us” images of people rolling up their sleeves and getting busy doing what they can do, what needs to be done –– helping one another, providing food, clothing and shelter, provides inspiration and solace for those directly involved, but also for those of us recognizing ourselves in this situation. As Frances Weller reminds us, in his book, The Wild Edge of Sorrow, “Everything we love we will lose…Everything is a gift, and nothing lasts.”

What Can We Do Now?

During the time I was researching responses to loss for my book, The Art of Grieving, I worked with several organizations of nuns. They shared a ritual they do when losses occur in their communities and beyond. This ritual begins with a question, one that each of us can ask ourselves in this situation of horrific losses. As we respond to what this event means in our own lives, to the lives of our loved ones, and to the future of life on this planet, we ask this question. With awareness of the possibilities of Secondary Losses that will no doubt follow the present ones, and of Anticipatory Loss as we look into the future, we ask and respectfully wait for answers to this question, “To what life are these losses calling us? To what life are they specifically calling me?”

Image and quotes from the AP article here: https://apnews.com/article/california-los-angeles-wildfires-photos-8c2f2767b3722ccbb98d6e78a563c1f4

Transitions

Here we are in the time of our yearly transition–looking back and remembering the past year. We’re saying good-bye to the old year, (the bearded man stooped over his cane) and while at the same time, greeting and looking ahead into this new year, (the diapered baby draped with the just-being-born-new year clearly labeled on him.) Depending on how many of these transitions you have had and what those experiences have been like in recent years, you may not want to give much attention to this event, just see it as a mark on the calendar. I’m sure it’s been that for me some years. But this year seemed special as I look back, enjoying the highlight of my book The Art of Grieving finally coming together enough to launch. From years of development––meditations, reflections, conversations, blogs, presentations, and collaborations with other artists to a book you can hold in your hand and formally launch–that’s a huge transition by itself. Many of you reading this note have been a part of these activities and the “village” it took to create this book––please accept my deepest gratitude. And I’d love to have you with me as I work to get it out into the larger world.

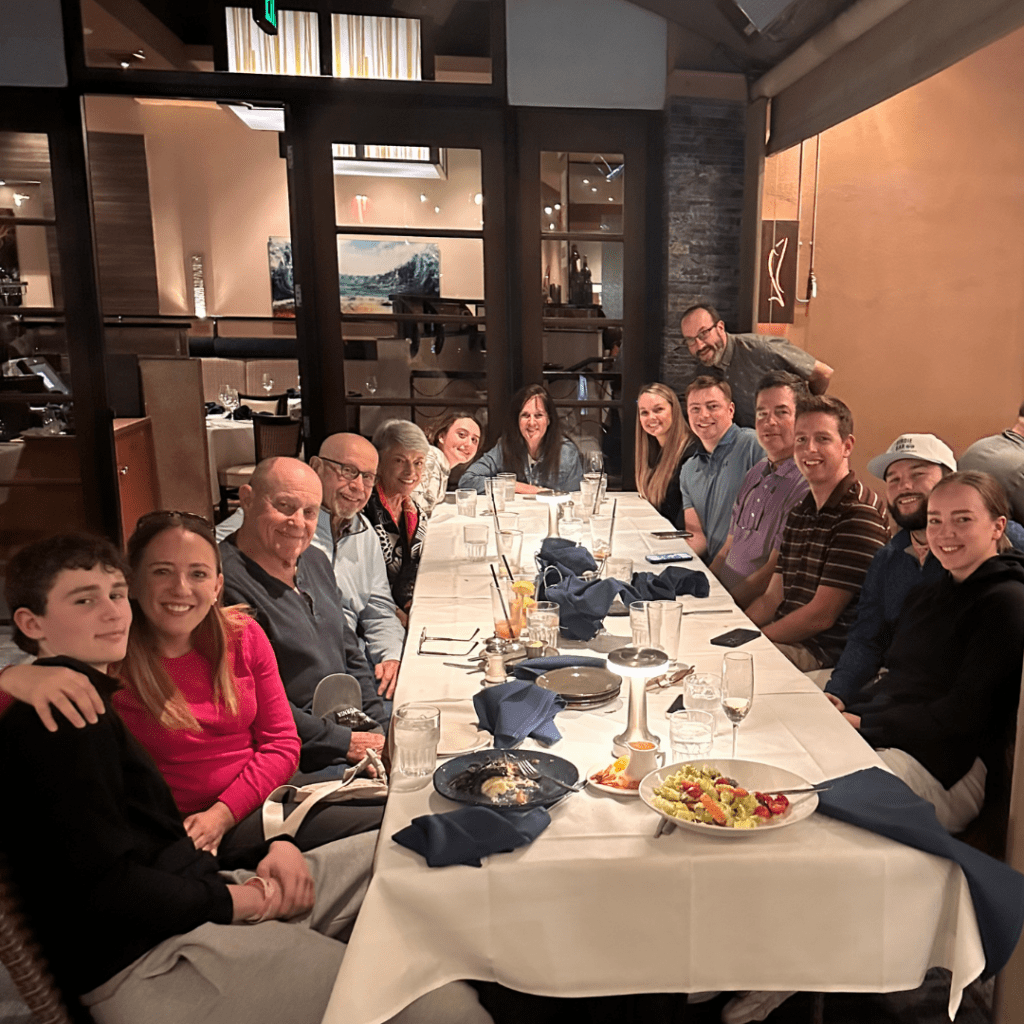

Our holiday family reunion is just coming to an end as I am writing this. Seventeen people came and went to and from Palm Springs California throughout the week from Pennsylvania and Nebraska, Massachusetts, Nevada, and New Mexico, and several towns in California. It took a spread sheet to figure out how many places to set at the dinner table for each meal. Despite the challenges there were multiple special moments of sharing memories of past reunions as well as opportunities to create new ones.

It will take a while to process the richness of this week though I got a head start during a phone conversation with a dear friend from back home a couple of days ago. She knows many back stories of the characters in my family tree, so her listening skills helped me recognize and acknowledge some major and minor miracles that occurred in our time together. There is such power in being surrounded by those to whom you belong and that belong to you.

We head for home this Thursday, quite tired, yet full of gratitude and ideas to follow up on in the coming year. I hope that your holidays have provided you with similar gifts as well. Going forward – Here are some of the classes, groups and keynote speeches I am looking forward to in 2025.

- Radical Self Care Series Class online with Christine Gautreaux resumes Tuesday January 7 2025 at 11:30 am eastern, recurring weekly

- Friday InterPlay Playshop online resumes January 10th 2025

- Art of Grieving online class begins Tuesday January 14, 2025, at 3 pm eastern time, recurring monthly on the second Tuesday of each month

- Keynote speech in Pittsburgh February 26, 2025 at Fox Chapel Rotary Club

- Keynote speech for Temple Rodof Shalom Brotherhood, Sunday May 4, 2025

- Pre-Conference Workshop at the International Expressive Arts Therapy Association Conference in Endicott College in Beverly, Mass. June 19, 2025

- Keynote at the IEATA 16th International Conference – Sunday June 22, 2025

Another note: My weekly blogs are moving to the Substack platform so watch for that soon. Meanwhile – I hope to connect with you in an online class or through a written communication, at a workshop or during a collaborative art project. May this New Year bring you long awaited gifts and opportunities for joyful collaborations.

The Gifts of Remembering

One of the cruelest outcomes of the “put it all behind you” and “move on with your life,” philosophy of managing loss is that we miss out on the gifts and life lessons that come through remembering. In a couple of recent events, I have been reminded of some of those gifts.

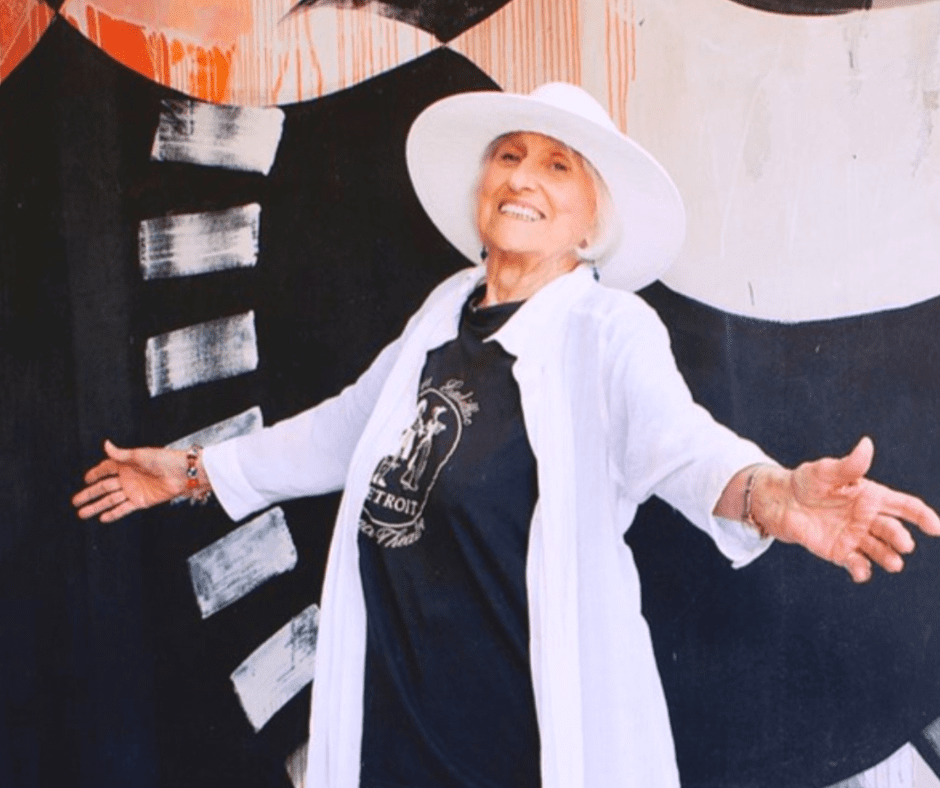

I moved away from Detroit Michigan more than 50 years ago, but through the years, I’ve stayed in touch with one of my dance teachers and mentors, Harriet Berg. Last week I was blessed to attend an online celebration of Harriet’s 100th Birthday. Her son and daughter-in-law did the arranging and with her help, the invitations.

We celebrants were former students, performers in her productions, or children of her close friends, now deceased. We traded stories of how she had influenced our lives, reliving some of those experiences as we described them. “You’re all over our house,” I told Harriet as my husband and I had pulled framed posters and photos from the walls to offer a “show and tell” about my life with Harriet. in those years when I was the choreographers’ assistant and founding member of Festival Dancers, her dance company out of the Jewish Community Center, she was a central figure in my life. “Here we are, Harriet, costumed to perform Charles Widman’s, ‘All About Women,’ that Widman himself taught us when you brought him to the Detroit area in the early 70’s.”

After the event was over, and we spoke of doing it again if that turns out to be possible, I realized that what we celebrants had created was a kind of memorial. As we sharing our memories with one another and with Harriet, we were creating a “living memorial,” sometimes called a “living funeral.” Such an event is done in the presence of a person who realizes that they are living in their final days. However, her final days did not seem imminent, at least to her as she reminded us that her father made it to 103. ‘I’m just trying to catch up with him,” she said.

Today is the one-year anniversary of my youngest sister Maureen’s unexpected death at 69. Tonight is a regular online gathering of members of The Wing & a Prayer Pittsburgh Players, my InterPlay performance troupe. Since these are the people who have companioned me on the long road that became The Art of Grieving, I’ve asked them to think of a particular loved one, now deceased and bring stories of that person to our meeting. We’ll use the dancing, singing, storytelling forms of InterPlay to celebrate these important people in your lives as we celebrate my sister Maureen. I’m especially interested in what situations or times in our present lives are we reminded of our special persons? How and when do they come to us now?

Grief, Money and Dirty Pain

To become resilient and grow from what happens to us, we must choose to face and metabolize the pain of loss. That’s what the art of grieving is. Psychotherapist Resmaa Menakem describes “clean pain’ as that which is faced and transformed while “Dirty Pain” is pain that is ignored or denied and stuck in our bodies. It interferes with our thoughts and ability to function, causing us to transmit the pain to others in an unfocused or purposefully planful way. It seems likely we’ve experienced a version of the latter this week.

The television broadcast is interrupted with breaking news. We see the shadowy figure of a hooded man pointing a gun with a silencer on it towards a figure of another man who is walking in front of him in the Wall Street section of NYC. We’re told that the second man was a 50-year-old health care executive, and that the hooded man shot him in the back and killed him.

We soon learn that three bullet casing were found, each labeled with a word, Deny, Defend, and Depose. Along with millions of other people in the US, I recognize these words as descriptive of the process health insurance companies use to deny patient and provider claims. As health care providers, my husband and I immediately added another D word –Delay. I was immediately transported to January 1992, when “managed care” entered the field of behavioral health, 5 years after we had established our own successful health care clinic. Divisions of health insurance companies become gatekeepers between providers and patients. Employees they hired determined what claims were allowed, and eventually how much was paid to those who provided the service. In the spiral of my own grief, I saw again the new furniture the health care company displayed proudly when I was at a meeting to discuss their paying our invoices in a timelier manner. While we waited, and juggled our own cash flow, I expressed my anger by researching, writing and presenting a paper at a health care conference on the 42 steps that now became necessary for employees of our company to accomplish in order for us to be paid. Any missteps out of order (service not pre-authorized) we would not get paid at all.

The public reaction of humor or scorn on social media to the murder seemed to be people offering the company “a dose of their own medicine,” ––reactions that shocked many people. But given the number of people who have been denied coverage for their own treatment or for the care of a loved one’s illness, it seems likely that the incident connected people to their own unprocessed pain. Add to that the fact that 500,000 people per year experience medical bankruptcy due to unpaid medical bills while health care executives are paid, as this gentleman was, 9 million dollars a year. It’s clear that our systems are broken and unjust and not serving individuals or the greater good.

Returning to Menakem’s powerful book,” My Grandmother’s Hands,” the path forward does not mean just providing more security for people working as executives in our healthcare system. Rather, we need to recognize and process the immense pain that the system causes (clean pain) and not just respond from our most wounded parts. (dirty pain). When enough people face the problem, we are more likely to heal ourselves and the systems that are meant to serve us.

The Power of Community Art

With all the media attention on the incoming president’s appointments, you may not have heard that this week, in honor of World AIDS Day 2024, sections of the AIDS memorial quilt were exhibited for the first time on the White House South Lawn. Our current President Joe Biden and First Lady Dr. Jill Biden hosted an event with survivors, their families, and advocates, offering a powerful tribute to those who have been lost to HIV/AIDS. Each square of the quilt has been handcrafted by friends and family members in memory of someone who died of AIDS since the disease came on the scene in the US in the 1980s. The AIDS Memorial Quilt began with nearly 2000 individual squares and was displayed for the first time in 1985. It now has 48000 panels, weighs 54 tons and spans 1.2 million square feet. In the nearly 40 years since it began, it has traveled and been exhibited in communities all over the US.

For those of us who have been impacted by HIV/AIDS, the expression, “better late than never applies” with this exhibition and with how long it took for the governmental authorities, politicians, and scientists to recognize the threat of AIDS and put resources into addressing it. Millions died, included our 31-year-old son, Kenneth. In my mother’s memoir, Warrior Mother: Fierce Love, Unbearable Loss and the Rituals that Heal there is a scene between Ken’s father and I, holding a conversation in a hospital corridor when we first learned of Ken’s diagnosis in 1993.

“How is it we get to go to the head of the class?” I spit the words into the atmosphere. “No ten years of symptom-free HIV status. No time to try alternative approaches to staying healthy. Nothing I know will be of any use now.”

George seems to be studying the patterns on the floor. “When are these people gonna wise up? They pay no attention to nutrition and then wonder why people get sick. “

” And where were the Centers for Disease Control? I raged. “Why didn’t they pay more attention to this disease when it first came on the scene?”

Finally looking me in the eye, former radio broadcaster George, said in his most professional newscaster cadence, “They ignored it because it was discovered in gay men.”

The AIDS Memorial Quilt has become the largest community arts project in history. It played a huge part in gaining support from health care authorities to address the disease and in eliminating the stigma that was part of what caused the disease to run rampant in the gay community in the US.

Why might this exhibition of these handcrafted art pieces sewn together and sprawled out on the White House Lawn be important at this time?

As one of the surviving family members, I’m glad to be reminded of the role an art piece such as this has played in helping the public identify the people behind the numbers when we learn of a communicable disease. Numbers are just numbers until an art piece shows us how many individuals they represent–the people behind the numbers. I also appreciate the opportunity to remember my son and his friends who became victims not only of the disease, but of the way it was handled by the governmental agencies that our taxpayer dollars had funded to keep us safe and healthy. After all we’ve been through it doesn’t seem the time to put people into leadership positions who have no experience or intention to achieve what these organizations are charted to do.

Here’s a link to Warrior Mother – https://amzn.to/3CZqJJj

View the AIDS Memorial Quilt here https://www.aidsmemorial.org/quilt

December 5, 2024, the White House Office of National AIDS Policy (ONAP) is convening a symposium to address core aspects of quality of life for people living with HIV. Portions of the summit can be viewed virtually Exit Disclaimer from 9:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. EST.

Grief at the Holidays

As the holidays approach, the subject of Grief becomes more common in articles, social media posts and advice columns. And for good reason. These special days of family celebration can be reminders of who will not be at the table this year. And perhaps as the rotation of another year comes around again, we are returned in memory to a time we still long for –when the children were small, when we lived in a part of the country were the weather seemed to cooperate with our holiday spirit, when gas was under $2, or when holiday gatherings did not involve the accommodation of complicated diets and eating programs. We may remember an idyllic time, which many never have existed, when we didn’t dread or try to avoid gathering at a common table with loved ones, some in deep grief over crushing losses while others ecstatic at the victory of their candidates.

So, what ancient recipes can we call upon to help us navigate these unsettling waters?

As a grief advocate and author of The Art of Grieving: How Art and Artmaking Help Us to Grieve and Live Our Best Lives I am often asked to speak or write about these dilemmas and challenges that are not unique or new to this year or this place. I grew up in Louisville Kentucky in the 1950s though my ancestors were not from there, so I was surprised to learn that during the war between the states, which was less than 100 years prior, Kentucky had been a border state, not officially joining the North or the South in the Civil War. I heard stories that were still being told of families who had sons that fought on different sides of the conflict. I remember thinking that must have made for difficult family gatherings.

There was a time when we knew how to grieve, when we understood as a culture that grief is not a stairway we climb where, we tick off a series of emotions on each step, and reaching the top, put our palms together and declare we are finished. There was a time when we knew that grief was not just a private matter, something to keep to oneself so as not to bring others down, but as a time to companion one another with compassion through disrupted terrain. To enter ritual space together for a time between the worlds, not to put the past behind us but to honor and keep close through the years to what we will always love.

I offer the visual art image of the spiral as an image that can help us grieve. A well-known author of the 20th century C.S. Lewis wrote of his own bereavement process in the book,” A Grief Observed.” He wrote it under another name, which tells us something of the unpopularity of the topic. He shared what I believe are elements of a universal model. “For in grief, nothing stays put. One keeps emerging from a phase but it always recurs. Round and round everything repeats. Am I going in circles or dare I hope I am on a spiral?”

The spiral is found in nature and in cultures worldwide, one of the oldest intuitive symbols of the physical, mental and spiritual development of a human life as it winds its way through the seasons of its years. Grief is the processing of our life experiences to determine what to cherish and what to hold dear, and what to let go of that will no longer serve us and the person we become in the future. For this we need a new perspective. The spiral brings us back to the same place each season but on a more evolved level. The anniversary of the loss occurs or a situation of remembering occurs, and the mourner now has another year of living without their loved one. They are viewing the situation from a different vantage point.

The festivities of the family gatherings provide opportunities to use the art of storytelling to bring those gone from our sight into the present moment and to honor their contribution. For those too young to have known the deceased, they are shown where they have come from, and what has allowed them to have their turn at life. Don’t worry about repeating your stories. In my family, we kids knew Auntie’s stories so well we could tell them ourselves, but we begged to hear them again and again. At the time, I thought it was the humor in them, and the fanciful way she told them by adding made-up new passages which we of course, would call her on. But now I think we needed to hear them again and again because the subtext of the stories was that our ancestors survived tough challenges so there’s a pretty good chance that we will survive tough things too.

If you live in the Pittsburgh area, I’d love to have you join me for an evening service on the theme of dealing with grief at holiday time. The program Blue Christmas is next Tuesday December 3rd at 7 pm in the chapel of First United Methodist Church 5401 Centre Ave, Pittsburgh, PA 15232.

Reentry

We’re finally getting the rain we’ve needed all summer which keeps me from my usual slow withdrawal from the outdoors as I return to Pittsburgh from the piney woods of east Texas. The fall women’s retreat was later than usual this year, and I needed it more than usual. But, what’s usual these days? Wisdom comes from what’s worked in the past, but I tell myself we’re in a different climate now, more unpredictable, requiring different creative practices. Sleeping in one’s own bed is still rewarding after a 3-hour drive to the airport followed by a 3-hour wait in the Admiral’s Club (a special treat now that I have my own frequent flyer membership card) followed by a 3-hour plane flight and, after my husband picks me up, a half hour car ride home.

In retrospect, the 3 days in the woods are always different, yet overwhelmingly the same for me since 1991. It’s always uncertain, who will show up, who will get to come. We call the names of those departed from this life, and those housebound or struggling in particular situations. We remind one another of other times, other years when we switched places on what native American’s call the Medicine Wheel and what I think of as the grief spiral. This time we included especially our country, and the larger world impacted by our country’s past, recent and future actions. We meditated on what is ours to do, in the long list of what needs to be done to continue serving life. One certainty–being in the Women’s Circle is always worth all the trouble and inconvenience it is to get there and back. And for a while, maybe a long while, I am different, always aware that I am because we are.

Invitation – I couldn’t take you to the woods with me, but this Sunday November 24th from 4 to 5:30 pm eastern time I’d love to have you join me and several other InterPlay artists as we meet on the Let’s Reimagine online platform. We’ll be exploring themes from my recent book, The Art of Grieving: How Art and Art-making Help Us Grieve and Life Our Best Lives.

Here’s the link to register:

https://letsreimagine.org/76768/the-art-of-grieving-how-art-art-making-help-us-grieve