If your work is in a so called, “creative field” you may already be familiar with the type of loss that I am focusing on today. For writers, performance artists, designers of various types that engage in projects requiring intense dedication and a considerable length of time –– once the project comes to an end, the producer or performer experiences loss and many questions of identity and purpose. The manuscript is finished, opening night has come and gone, the deliverables have been delivered. The completion itself is life changing.

If your work is in a so called, “creative field” you may already be familiar with the type of loss that I am focusing on today. For writers, performance artists, designers of various types that engage in projects requiring intense dedication and a considerable length of time –– once the project comes to an end, the producer or performer experiences loss and many questions of identity and purpose. The manuscript is finished, opening night has come and gone, the deliverables have been delivered. The completion itself is life changing.

Who are we now that the structure provided to our lives by the project is gone? Our creative production now needs to be distributed or presented and received by its audience, but much is required of its creator to make that happen. And this getting our work out into the larger world makes very different demands on us than those demands of the creative phase. How has the effort to create this product or event changed us? Are we being changed further by the comments of friends and family members, and in the official reviews of people who claim to know? It seems we are risking encouragement and discouragement, elation and disappointment. In this new phase it can feel like we are risking losing ourselves.

When I was in high school and the final night of the dance concert wrapped up, or the cast party for the school play was over, I noticed the mix of emotions that accompanied this bittersweet time. There was the self-satisfaction of accomplishment, “we did it” and the sadness of saying goodbye to the people and activities that had been the focus of many months of my life.

As a writer, I’ve known the reluctance to decide that I have come to the end. Might there be something else this piece needs to stand on its own and deliver the messages I have struggled for months or years to express? A friend who writes poetry told me that as she edits the poem, again and again, (and poets are really picky about where the comma goes), when the arrangement of the words returns to the same place a third time, she declares the poem done.

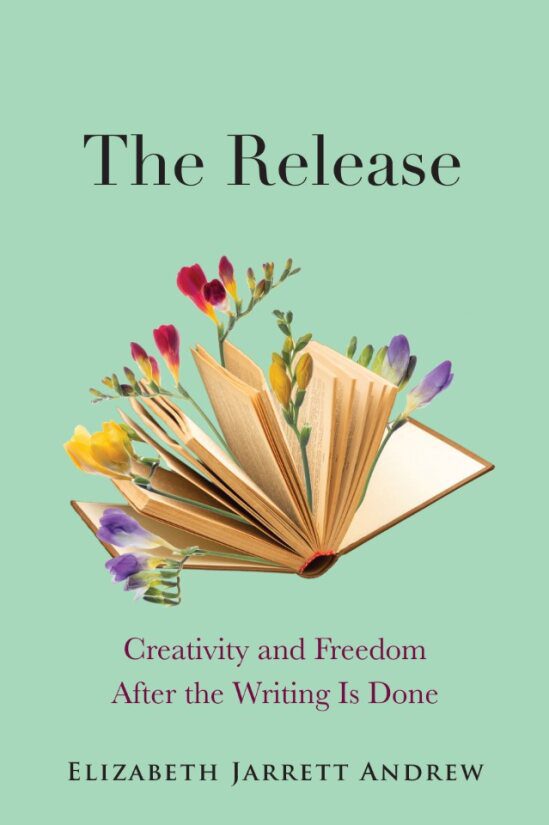

This after phase of a creative project is not spoken of as often as the crafting part, yet it seems to be as important to the work and the wellbeing of the work’s creator. As a writer who has just released my 4th book the end of May, Elizabeth Jarrett Andrew’s new book The Release: Creativity and Freedom After the Writing is Done has come just in time. If like me, once you have completed the production phase of your creative work, it now demands more from you than you feel comfortable and skilled enough to give––Elizabeth’s new guidebook will be just right for you too. She offers her releasing process to help “spare us some grief,” so we may form habits “that support our project’s final flourishing and keep us creatively engaged.” As I work through the suggested activities in the book, I hope to find personal answers to the critical questions The Release raises. “Is it possible to approach the period after finishing (one’s work of art) as an opportunity for continued creativity? What might it look like to stay grounded as we share our work with its intended audience?”

I recommend this book to anyone who has suffered the depression and anxiety that often accompanies getting creative work out into the larger world. Consider not only getting a copy for yourself but gifting the book to young writers and artists in your community to spare them the grief we experienced creatives know all too well.

Another way to help ––It takes a village to get a book or art project to its intended audience so if you get the book and find it useful, please leave a three-sentence review on the bottom of the book’s Amazon page. It takes a minimum number of reviews to have the search engine recommend a book when people begin shopping for a book on a particular subject on the Amazon platform. While you’re there, I would be most grateful if you would become a part of my book village by leaving a three-sentence review on the amazon page for my new book, The Art of Grieving: How Art and Artmaking Help Us Grieve and Live Our Best Lives. With both these actions, you will play an important part in making what Elizabeth calls, “the transformational dimension of writing” available to more people who seek it.