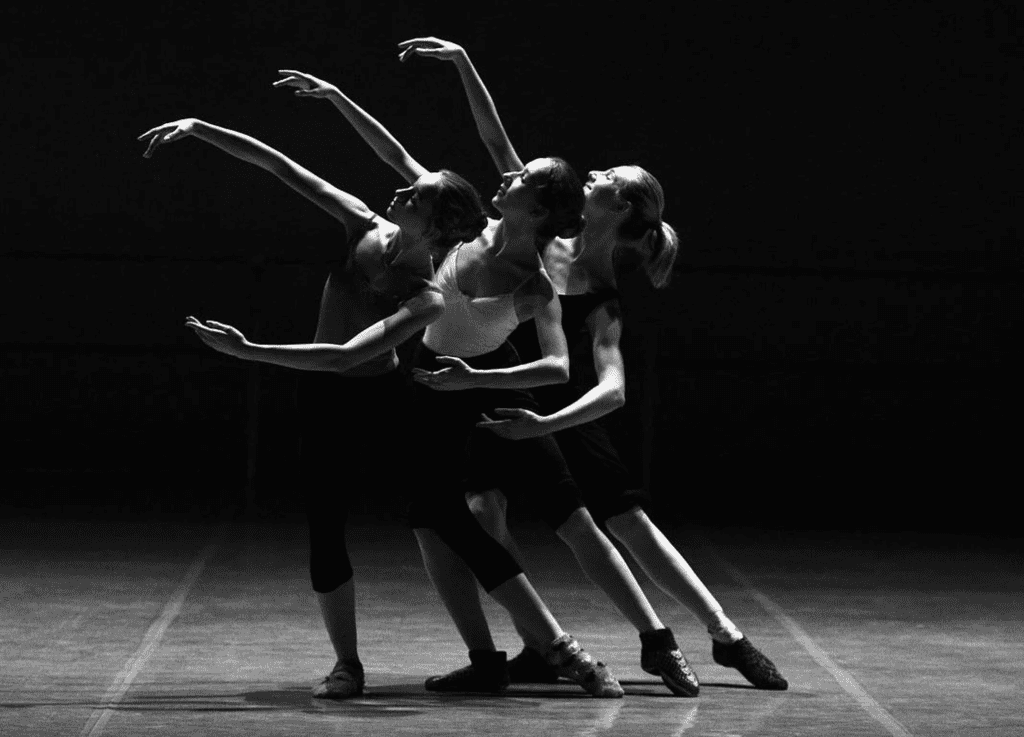

My fellow InterPlay improv artists and I often play with individual and cultural challenging topics–grief and sorrow, love and loss, violence, and racism, and putting an ending to them. Using a system rooted in dance, our individual and collective expression comes from our bodies’ wisdom, knitted together in forms of creative connection. Whether we’re online or in person, after we’ve created and performed a movement piece together, someone will say, “that was so satisfying,” and we all agree that it was.

My fellow InterPlay improv artists and I often play with individual and cultural challenging topics–grief and sorrow, love and loss, violence, and racism, and putting an ending to them. Using a system rooted in dance, our individual and collective expression comes from our bodies’ wisdom, knitted together in forms of creative connection. Whether we’re online or in person, after we’ve created and performed a movement piece together, someone will say, “that was so satisfying,” and we all agree that it was.

Though the popular notion of dance is that it is an energetic celebration of positive moments in life – think weddings, birthdays and graduations, dance can also be an act of mourning, a full-bodied expression of life’s challenges and ways to grapple with them. I learned this initially when I danced at my best friend Rose’s funeral after she died of breast cancer and a bit later, at my 31-year-old son’s memorial service, when he died of AIDS 25 years ago this week. As a dancer, and later a dancing social worker, I saw what bringing dance into scenarios of sorrow does for the families and loved ones of the newly deceased –the time when people feel exhausted, their energy spent. Sometimes dance is something the mourners do, as when my siblings and I formed a circle and performed a folk Dance of Universal Peace around the remains of our 26-year-old kid brother who’d body had been returned to our parents after he’d been missing for 2 ½ years. In that time of horror and disintegration, moving in rhythmic connection with one another was a balm of reassurance that moving beyond that moment would be possible.

Sometimes dance is performed on behalf of the mourners. My brother Miles, knowing of my dedication to the role that the arts can play in helping us grieve, sent me the link to an amazing example of what witnessing someone dancing grief can be like. The three-minute film, crafted from over 30 hours of footage is a New Yorker Documentary, titled “Unspoken.” One of dance’s biggest advantages is that it does not rely on words but comes from a deeper place of clear awareness. As each of the arts do, dance connects to universal themes and large-scale human dilemmas. The film begins with the international choreographer, Paul Lightfoot, speaking about how the dance he was making could be a way for him to say goodbye to his father. He was unable to do that when his father died in a hospital during Covid when visitors were not allowed. Filmmaker William Armstrong, who was looking for a story to tell that reflected the uncertainty and fear of this cultural moment, came together with Lightfoot, musician Alexander McKensie and an especially athletic and exquisitely skilled male dancer. Viewing the dance that was constructed and performed on zoom takes we the witness, through the magic of motor neurons in our own bodies, on a full-bodied expressive journey of loss and longing, sorrow, and invigorating resistance, ending in quiet acceptance of what is lost and found.

How does it work? I have found in helping people process and metabolize their losses as well as in processing and metabolizing my own losses that some stories are too big for one body to hold. The story must be held in a community of bodies. When that happens, there is relief, a sense of satisfaction, even a glimmer of hope that we will be able to move forward in our lives.

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/the-new-yorker-documentary/dancing-a-story-of-love-and-grief