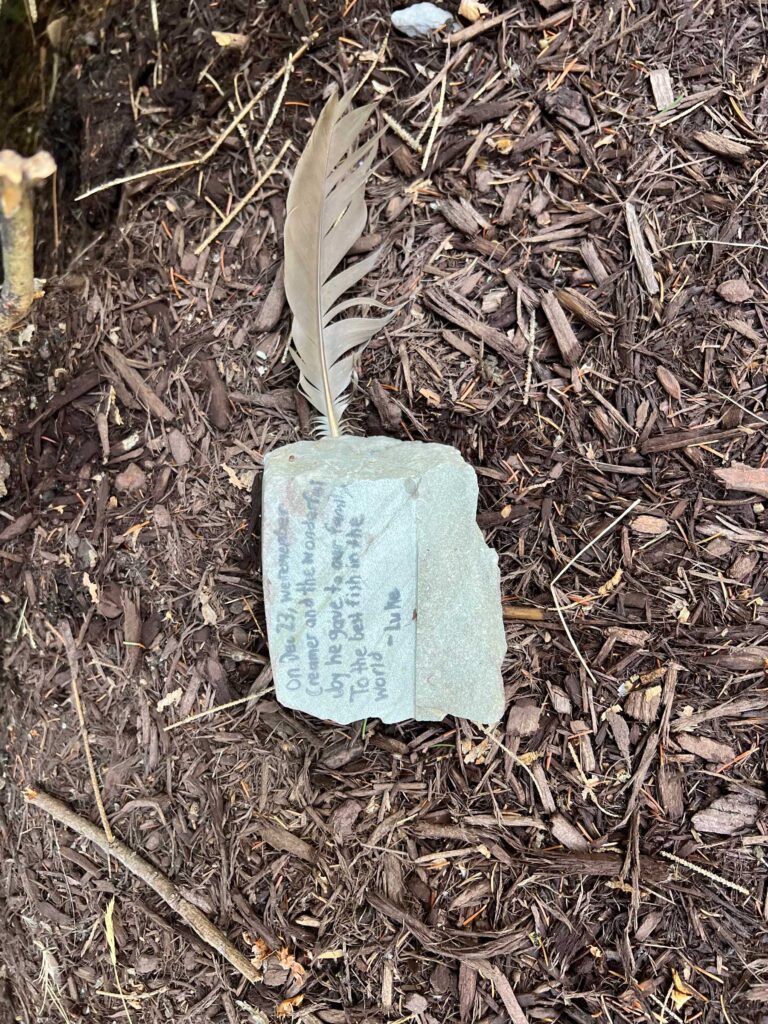

As I was walking my dog Cody one morning this summer, he started to pay attention to something underneath one of the bushes that line a communal driveway in our neighborhood. Looking over at the spot I identified a small rock and a feather, and moving closer, realized that someone had purposefully placed these items to mark this particular spot. Reading the inscription on the rock I learned that Cody and I had stumbled onto a now sacred space–the gravesite of a child’s pet. I imagined the ceremony that likely took place there as the child and his parents carried their loved one in formal procession from their home to this resting place. As the note on the rock detailed, “we remember the wonderful joy he gave to our family -the best fish in the whole world!”

As I was walking my dog Cody one morning this summer, he started to pay attention to something underneath one of the bushes that line a communal driveway in our neighborhood. Looking over at the spot I identified a small rock and a feather, and moving closer, realized that someone had purposefully placed these items to mark this particular spot. Reading the inscription on the rock I learned that Cody and I had stumbled onto a now sacred space–the gravesite of a child’s pet. I imagined the ceremony that likely took place there as the child and his parents carried their loved one in formal procession from their home to this resting place. As the note on the rock detailed, “we remember the wonderful joy he gave to our family -the best fish in the whole world!”

The first experience young children have with grief and loss is likely to be the death of a pet. The first impulse of parents is likely to be to try and protect their children from the feelings that a loss naturally engenders–sadness, grief, and anguish, or perhaps anger. Our culture has made grave errors in attempting to protect children by not including them in funerals or restricting them from the bedside of a dying loved one or trying to spare them from the truth that someone is likely to die soon. As I saw with many therapy clients, the negative effect of these “protective” measures can rob the person of the opportunity to observe and develop lifelong skills to effectively cope with loss.

The parents of this child have clearly made the most of this teaching moment. Communal ritual is one of the most time-honored methods of grieving and companioning others through their grief. The most prominent gift of grieving is the gratitude it opens in our hearts for the life of the loved one–person or pet, and for the time we had with them.

Opening our lens to a wider view of how some people in our country are having trouble successfully grieving the loss of their preferred candidate, (or the candidate’s own difficulty accepting his loss) we see how important these skills of grieving are to our personal and communal welfare. Though it’s a good idea to start early learning these skills, I believe it’s never too late. As a contribution to that effort, I’m passing along the following wisdom my husband found on Facebook.

Buddha’s Four Noble Truths for a 4-year-old

- Sometimes people feel sad.

- Sometimes what makes people sad is not getting something they want or getting something, they don’t want.

- There is a way to not feel so sad about not getting something you want or getting something, that you don’t want.

- The way is to not think so much about what you want, but instead think about how you can be kind and helpful to your family, your teachers, your friends, other people, animals, bugs, and everything that lives.