Most communication, especially for teachers and writers involves finding the right words. As a therapist whose first profession was as a dancer, I often use expressive arts to help people connect with the creative side of themselves and to help process the experiences that life is currently presenting them. Frequently these challenges involve loss or the anticipation of losing something or someone that feels essential to life itself.

For the past 30 + years I’ve used the modal expressive art forms of InterPlay which involve storytelling, dancing, music, voice, and stillness. These art forms get people in their bodies and more fully into the present moment–the only place where transformation can occur. These forms can be done in a one-on-one situation, but their power is enhanced when they happen in a group. People would ask, “who are these groups for?” and my answer would be, “anyone I can talk into them.”

As a grief advocate, I have not always been able to find the right words to convince people that grief, when experienced in the presence of loving companions is not something to fear or run away from as Western culture has led us to believe. Misconceptions about the grieving process abound which is no small matter since grieving well is our essential connection to what really matters and to a meaningful vital future life.

As a mental health professional, I had been taught Elizabeth Kubler-Ross’s 5 stage model of grief, the one that continues to appear in most every journalist’s article about grief. The model first appeared when the Swiss-born American psychiatrist published her first book, On Death and Dying in 1969. It was a theory to encourage psychological counseling for the dying. How it has become most everyone’s model of processing the emotions of grief has been a mystery to me. Researcher, John Bernau in his article, “The institutionalization of Kubler-Ross’s Five Stage Model of Death and Dying,” suggests it was “early scientific interest and commercial promotion” that is responsible for the popularity of the model and notes its current use as a model is “to understand everything from rent prices to COVID-19.”

Besides the fact that Western culture tries to reduce everything to a step by step, one and done intellectual process, my curiosity has led me to focus on the role of the angular graphic image of the model featured in the original edition. After all, we know the power of an image, it’s worth a thousand words. Reading from left to right we view the shape of upward stairsteps, each named with a different emotion on each step– “denial,” “bargaining,” “anger,” “depression.” Arriving at the top landing we read the word “acceptance.” As a dancer, I can almost feel the action of climbing the stairs, ticking off each emotion and then, arriving at the top–brushing the palms of my hands together in the gesture of completion. “I did it. I’ve arrived. It is finished.”

Noting the quotation marks around the word “Stage” in the phrase “’Stages” of Grief” underneath the image, I’m certain that Kubler-Ross did not intend for this process to be viewed as a series of linear steps or stations, but in my own work with clients, I feel it necessary to point out that though all the feelings listed in the model could and often do occur in the long arch of grieving, there are many emotions missing including critical ones like anguish and sorrow. And though I usually wait awhile before introducing the notion, I eventually remind people that it’s possible to feel more than one emotion at the same time. Eventually experience teaches all mourners that grieving bears little resemblance to this organized illustration of the grieving process, leaving us longing for a model that comes closer to our actual experiences of grief and loss.

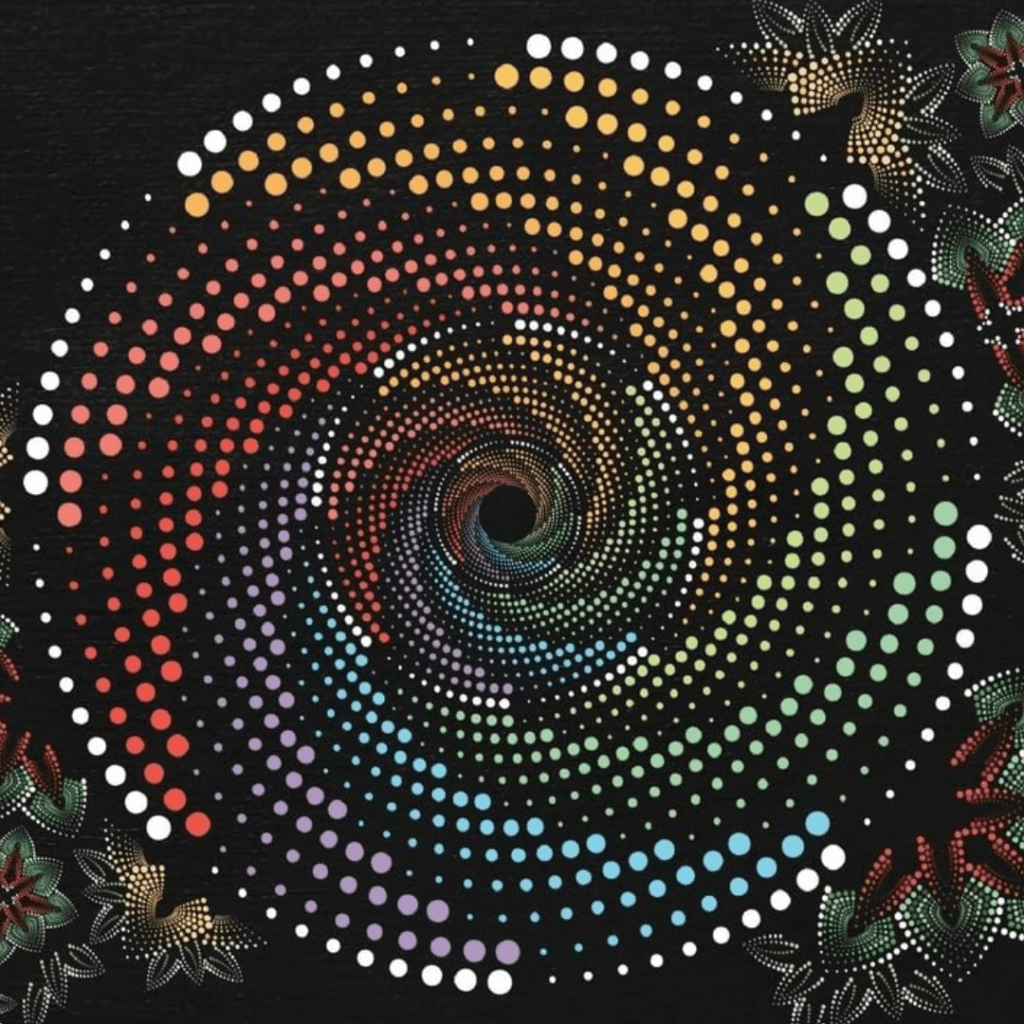

I discovered a better image for the grieving process while during the research for my recent book, The Art of Grieving: How Art and Artmaking Help Us Grieve and Live Our Best Lives. In “A Grief Observed” by C. S. Lewis, which was published in 1961, nearly a decade before Kubler-Ross’s work, he shared in his description of his own experience of grief, what I’ve come to believe to be elements of a universal model. It fits better with the experiences of mourners and helps explain some of the odd occurrences people in early grief report. “For in grief nothing ‘stays put. ‘One keeps on emerging from a phase, but it always recurs. Round and round, everything repeats. Am I going in circles, or dare I hope, I am on a spiral.”

Found in cultures worldwide, the spiral is one of the oldest intuitive images and symbols of the physical, mental, and spiritual development of a human life as it winds its way through the seasons of its years. Representing the cycle of the seasons and the cycles of life, growth, and change, the spiral brings us back to the same place each season but on a more evolved level, offering new perspectives with each turn. The anniversary of the loss occurs, but the mourner now has had another year of living without their beloved, and they are viewing the situation from a different vantage point.

As the cover of my new book features a multicolored image of a spiral designed by a Pittsburgh artist, Crista Varley I have been engaged in a kind of unintended informal experiment. The spiral image seems to captivate people who view it, drawing them in to explore the subject with me or the contents within. One art museum carrying the book placed it near the checkout counter and found the image stimulated impulse purchases, sometimes as gifts to friends dealing with grief. Other books of mine on grief, like my 2013 mother’s memoir, Warrior Mother: Fierce Love, Unbearable Loss and the Rituals that Heal did not stimulate such a welcoming response.