This month is Domestic Violence Awareness Month. National efforts to raise awareness of spousal, domestic, and dating violence began in 1987, though my awareness of this issue began in the early 80s. A woman professor, a mentor of mine, and a woman I very much admired told me of her volunteer work on the board of one of the first women’s shelters in the country. When I asked this brilliant articulate woman how she got involved, she told me that she herself had been an abused wife. To use an expression, common in those days, “this blew my mind.” She so did not fit my image of who might be involved in such a situation.

This month is Domestic Violence Awareness Month. National efforts to raise awareness of spousal, domestic, and dating violence began in 1987, though my awareness of this issue began in the early 80s. A woman professor, a mentor of mine, and a woman I very much admired told me of her volunteer work on the board of one of the first women’s shelters in the country. When I asked this brilliant articulate woman how she got involved, she told me that she herself had been an abused wife. To use an expression, common in those days, “this blew my mind.” She so did not fit my image of who might be involved in such a situation.

Hopeful, in the nearly 40 years since congress passed Public Law 101-112 officially designating October as National Domestic Violence Awareness Month, as a culture we have become more aware and more understanding of what domestic violence is, who can be its victims, and pervasive it is in our culture, and how to address it. Not surprisingly, Afghanistan is the country with the most domestic violence, mostly against women (60%), a strong indicator that the status of women in a culture impacts the extent of violence against them. In the US 22% of women and 19.3% of men are assaulted by their partners at least once in their lifetime. Higher rates of intimate partner violence happen among younger dating populations, which has led to programs for prevention starting early, beginning with anti-bullying programs in elementary, middle, and high schools.

Programs to engage men and boys have proved helpful, moving good men from having an interest in the matter to making an investment in standing up against the bullying and terroristic attitudes and behaviors of their perpetrating brothers. In the Pittsburgh community a few years ago, my husband got involved in a project where men, on Father’s Day, took a pledge to not tolerate physical and/or emotional abuse in their family and work environments. This led to some uncomfortable but brave conversations in our family, and sometimes among friends.

“Shut down locker room talk,” said Kristy Trautmann of the FISA Foundation. “If you hear disrespectful comments or jokes, say ‘that’s not funny, don’t talk like that in front of me.”

Like the anti-terrorist campaign at airports where people are encouraged “if you see something, say something,” breaking the code of silence is important because such disrespect and violence affects us all.

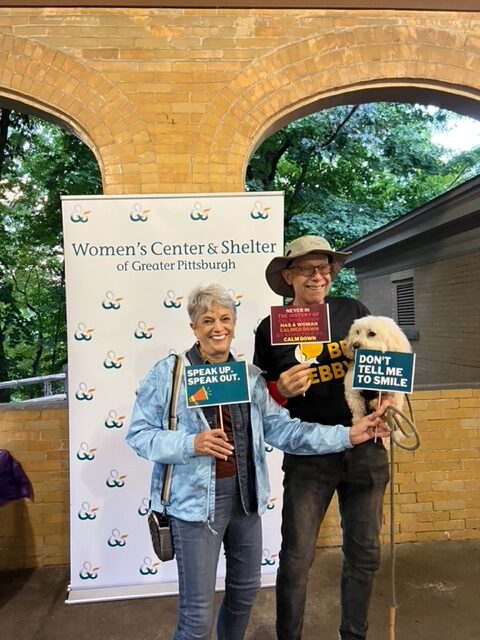

My husband got involved in another project to increase awareness and decrease violence against women, “Standing Firm, the Business Case to End Partner Violence,” now affiliated with the Pittsburgh Women’s Center and Shelter. Employers have a critical role to play in protecting the workplace from violence. Four women a day in the US lose their lives at the hands of someone with whom they once had a bond of trust and love. Violence is more likely to happen in the workplace once a woman finds safe haven in a shelter because her aggressor doesn’t know where she lives, but he knows where she works.

Through the years one of the most difficult issues to understand is expressed in the question, “Why doesn’t she just leave.” As I’ve looked more closely at family estrangements of all types, I’ve wondered if looking at partner violence through the lens of grief might help answer this question. People in close relationships often reveal to one another, and see one another, at their best and at their worst. Sometimes these two aspects are not well integrated with one another, so it seems like the person is two people. One day the person you met and fell in love with, or the person you raised, or knew in a positive way for years begins treating you as an enemy, and the source of all their unhappiness. Then, perhaps they apologize or, even if they don’t, they seem to regret their behavior and begin treating you in a more positive way. Now it seems the person you love has returned and you reinvest in the relationship. Then the cycle begins all over again. For some people, it is hard to give up on those we love. If the person dies, we are forced to separate. What’s needed in that case is called companioning – support and love to accept that the person we love is gone from our sight, and support as we reconfigure our new life without them. When the person is still alive, but no longer operates out of love and becomes a danger to themselves and others, and to us, their partner needs even more support to separate and begin reconfiguring a new life without them.

Sheila

Know someone who needs help check out http://www.nrcdv.org/ and

https://www.hrsa.gov/behavioral-health/national–resource–center–domestic–violence